The fashion identities in the context of a wider conversation about American nationhood, to whom it belongs and what belonging means. Race and ethnicity, class, gender, and sexuality are all staple ingredients in this conversation. They are salient aspects of social being from which economic practices, political policies, and popular discourses create “Americans.” Because all of these facets of social being have such significant meaning on a national scale, they also have major consequences for both individuals and groups in terms of their success and well-being, as well as how they perceive themselves socially and politically.

The history of Jews in the United States is one of racial change that provides useful insights on race in America. Prevailing classifications have sometimes assigned Jews to the white race and at other times have created an off-white racial designation for them. Those changes in racial assignment have shaped the ways American Jews of different eras have constructed their ethnoracial identities. Brodkin illustrates these changes through an analysis of her own family’s multi-generational experience. She shows how Jews experience a kind of double vision that comes from racial middleness: on the one hand, marginality with regard to whiteness; on the other, whiteness and belonging with regard to blackness.

Class and gender are key elements of race-making in American history. Brodkin suggests that this country’s racial assignment of individuals and groupsconstitutes an institutionalized system of occupational and residential segregation, is a key element in misguided public policy, and serves as a pernicious foundational principle in the construction of nationhood. Alternatives available to non-white and alien “others” have been either to whiten or to be consigned to an inferior underclass unworthy of full citizenship. The American ethnoracial map-who is assigned to each of these poles-is continually changing, although the binary of black and white is not. As a result, the structure within which Americans form their ethnoracial, gender, and class identities is distressingly stable. Brodkin questions the means by which Americans construct their political identities and what is required to weaken the hold of this governing myth.

Related Posts

SRKP: intro vow of now vows for

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit. Donec odio. Quisque volutpat mattis eros. Nullam malesuada erat ut turpis. Suspendisse urna nibh, viverra non, semper suscipit, posuere a,...

SRKP: Ask what good to do about us

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit. Donec odio. Quisque volutpat mattis eros. Nullam malesuada erat ut turpis. Suspendisse urna nibh, viverra non, semper suscipit, posuere a,...

SRKP: opt out of scary tech try

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit. Donec odio. Quisque volutpat mattis eros. Nullam malesuada erat ut turpis. Suspendisse urna nibh, viverra non, semper suscipit, posuere a,...

The Real Motivation Behind Police Militarization…

In the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, and most of the 1980s the average Police Officer was equipped with a .38 Revolver (that needed to be reloaded after 6 shots), a wooden billy-club, & no vest or...

AfroSexism & Misogynoir: BLK Ego Defense Mechanisms

When the White/Arab Slave Masters Raped, Brutalized, and Mutilated BLK Women the BLK Man was left with one of two options.... 1. Kill that Muthafucka!...(and face a brutal, agonizing death). ...

Positive Aspects of My Negativity by Bro. Diallo

People who say I'm all about "Negativity;" yall couldn't be more off base. I will admit, most of my Social Media content is rather unpleasant, across all platforms, but that's only because I feel...

Neither Integration Nor Separation Will Free Us!

Seeking Equality with Whites is absurd cuz if Whites allowed for Equality & surrendered their political/economic/social/cultural/military/psychological advantage they'd loose all of the shit...

On Human Meat Consumption

Humans who consume meat are not Carnivores, nor are they Omnivores; they are Parasites. Carnivores & Omnivores prey on the sick, weak, injured, and old animal, Carnivores and Omnivores...

Fuck Waka Flocka!

Yo! Fuck Waka Flocka! Fuck all of you ABA (Anything But African) fucking Coons! Now he tryna walk back is ignorant as statements while throwing in a little Classism to boot. He think cuz...

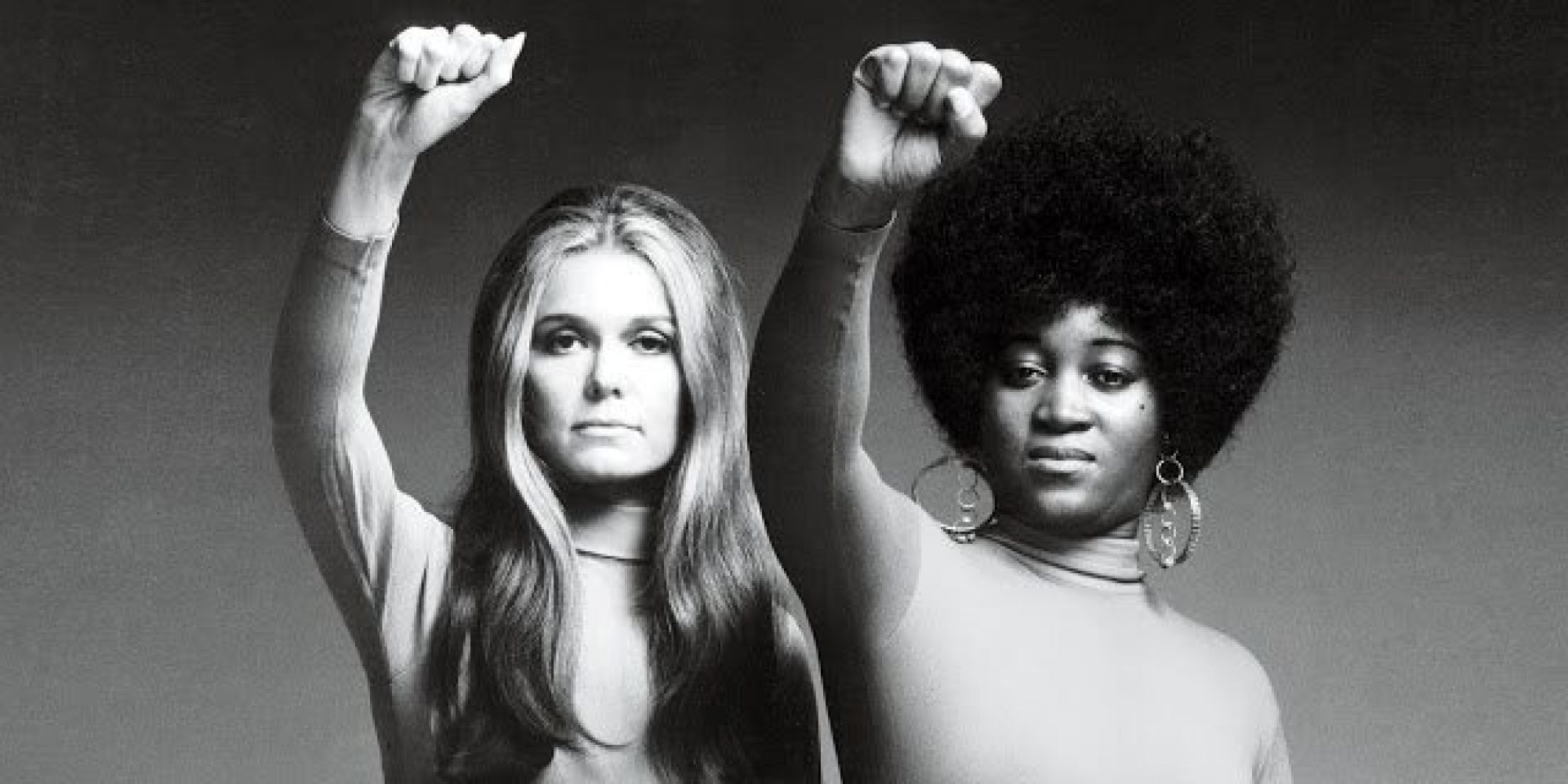

The Black Feminist Dilemma

Black Feminist refused to admit that Feminism is about Gender Equality, that Feminist have been fighting since the Women's sufferage Movement for equal rights, opportunity, and pay with (White) men!...

Protocols for the Prevention of Gayafication!

Ladies, I got some really bad news for yall: Due to the insidious conspiracy constructed and carried out by the Gay Agenda, and supported by all of you women; to turn us Manly, Macho, Heterosexual...

Why Trump Will Be Triumphant & Obama Wasn’t….

Look at how Trump's base is holding his dumb ass to task, how they are on him every time he deviates from their agenda, when he falls short, when he tries to compromises with their political...

What is the difference between Pan-Africanism and African Internationalism? Was Pan-Africanism attack on Garvey’s effort to unify Africa and African people? I just thought they were the same thing, different name?

As far as I know; the Uhuru movement came up with AI cuz they wanted their own isolated segment of the Struggle, its really just about branding and ownership….at the core, I’m sorry to say.I...

Thoughts on the the Nate Parker controversy?

Which controversy? The rape allegations?His response (or lack thereof) to the rape allegations?The Tomification of an African Icon?A rift that emerged between Black Feminist & Black Puritans...

Why do you promote the idea that only whites are mass aggressors on other civilizations when for literally 2300 years Europe, the Middle East and Northern Africa were overtaken back and forth by massive asian civilizations commiting slaving and genocide? It seems to me that any civilization once it becomes concentrated enough to brainwash itself with its own form of racialism or nationalism ends up this way and it’s only that western white civilization is the most recent example.

Oh hush, tryna disguise your White Deflection as a simple question.Don’t no fucking body “promote” shit about White people, we fucking live under White aggression, under the threat of nuclear...

Brother Diallo, what are some films you found enlightening, important or even entertaining? You’ve made list of books everyone should read but you haven’t made one for films.

Just off the dome, this is what I’d recommend…Romero…Lumumba…The Harder They Come…the spook who sat by the door…Sarraounia…Kirikou & the...

nnsep-this-new-negro-is-outraged-by-black

#NNSEP : This New Negro is outraged by Black looters, but has no problem being a a lawful, patriotic citizen of a criminal nation on stolen lands. #ExposeIsolateExpell?

From A Pan African perspective where is civilization on the planet headed?

Civilization (As the West defines and imposes it) is headed towards collapse, total and permanent collapse; which is a good thing in the long run. Civilization literally means: More people occupying...

I am still in the middle of reading The Iceman Inheritance, but I have some questions I’d like to ask as well as knowing what, if any, criticisms you have of the text. 1. Bradley states the African and the Asians succumbed to Europeans because of “advanced technology” the Europeans had. What technology is he speaking of? Also, he states that the Black Africans enslaved the Capoids, or South Africans much like we were enslaved. What do you know about this period in African history?

Bradley stated that “White Aggression” is the sole cause of their expansion and domination over all other Races. He also stated that Whites had no higher level of civilization, intellect,...

What did you say in your lost radio show? The one you didn’t record?

Shiiid, I wish I know, if I had that kinda recall I wouldn’t have to record the show. LOL!Sometimes you can catch the Fb Live recording of the show that didn’t get picked up by the janky...

Is hate a good thing?

“If someone hates you, hate em back! It’s healthy!” - Del Jones“You Must hate your enemies.” - Che Guevara Hate is an emotion, I have warned against classifying any emotion as inherently...

Comrade Diallo, Why are white folk so psychopathic? Seriously what is wrong with these people? I can’t understand this shit. There’s levels to how deranged these whites are. These folk past and present create volumes of material showing each and every time they engage in violent mindless acts how they enjoy that shit yet seriously claim that Blacks are responsible for all social ills, are genetically inferior and have low iq? Are these people really this crazy and dumb or are they pretending?

Short Answer: I don’t fucking know, I wish I did, but it baffles me too.Lone Answer:There are several White Scholars, Psychologist, Anthropologist, Scientist, and Philosophers that offer insight in...

How were AAs able to progress after slavery and build communities such as the Black Wall Street? Why weren’t people in the islands able to do so?

African-Americans were able to build communities such as Black Wall Street & Rosewood; as well as make great strides in industry and state-craft in the Reconstruction Era because we were engage...

How do tote the line between race and class to form a radical movement?

We don’t tote the line, we engage on both fronts simultaneously. We work to Dismantle the Systems and Institutions of White Domination and we work to destroy Class Contradictions and Hierarchies...

what can blacks learn from countries such as norway and denmark? what policies can we adapt to build up developing black nations?

The Social Democracies of Western Europe can’t really teach African shit that African don’t already know. They can teach us that White Liberals is as willing to sustain and advance the Systems...

What is with this celebration of Maxine Waters as a political figure? Did she start representing the best interests of African people? Has she climbed out of the back pocket of Israel? If I had to have an “Auntie” in Congress, it would be Cynthia McKinney, not Waters. Why do we continue to celebrate people like Waters and her ilk?

Maxine is truly a tragic figure. She’s kind of a Political Pied Piper for Blacks; here’s how:MW was elected right on the cusp of the Clinton Era, Clinton had a plan to move the Democratic Party...

The Public Has a Right to Know About Atrocities Happening Behind Prison Walls

The Public Has a Right to Know About Atrocities Happening Behind Prison Walls

How did Dr. Amos Wilson die? Should we expect it to be the work of our oppressors when our liberation fighters die under mysterious circumstances?

I never had the opportunity to meet Dr. Wilson, he passed not too long after I moved to NYC, so I didn’t know him personally, but I was well aware of his research and writings. Dr. Phil Valentine,...

How Journalists Covered the Rise of Mussolini and Hitler

How Journalists Covered the Rise of Mussolini and Hitlercricketcat9: nevernewyear: kmnml: annetdonahue: youngblackfeminist: valeria2067: glorious-spoon: giandujakiss: So the Smithsonian posted this...

Comrade Diallo, you seen that hashtag #altrightmeans? From a pan African perspective what does that hashtag mean to you?

It don’t really mean shit, Racist are always re-branding and reworking their shit; but it’s all the same in the end.The AltRight isn’t an alternative to the mainstream Right, it’s just...

Report: Monsanto Skipped Important Testing On Weed Killer That’s Now Killing Crops

Report: Monsanto Skipped Important Testing On Weed Killer That’s Now Killing Crops

Brother Diallo, since Trump and Kim are threatening each other with nuclear annihilation, what is the likelihood of full scale nuclear war in the next 100 years? You have children? Do you think they will live to see nukes being used by an insane piece of shit?

diallokenyatta: First off, the earth has already endured a Nuclear Holocaust. White Nations have been building and exploding Nuclear bombs, creating and spreading nuclear waste since 1945; that was...

Slutty Settler Colonialism

Who else supports Slutty Settler Colonialism? Who supports Progressives Militarism? Who supports Gender Neutral Genocide? I don’t even know where to start with this bullshit…., hell, if I have...

What are your thoughts on our ancestor Frances Cress Welsing white genetic annihilation theory concept?

Well, TBH it doesn’t really hold up on it’s own.Dr. FCW states that Whites are driven to dominate the world due to their inability to reproduce themselves with other Races, that their genetic...

Post your poem a revolution deferred.

I couldn’t find it, if you got a copy of it feel free to share, but I got a consolation poem that I’ve never shared. It’s old too.I wanted to write a poem about fans who kidnapped their...

Diallo, I know you said you at pro-homosexuality. Do you really believe that there is no Gay agenda that’s affecting the black community. And also please explain how you can be pro homosexuality and a pan Africanist at the same time because to me the 2 does not mix.

How many ways can you keep asking me the same question Anon?Here we go Again:There is no Gay Agenda targeting the Black Community, I’ve read many off those who make this assertion, but none of it...

Brother Diallo, why are you an atheist?

I’m an Atheist because there is no evidence of God; the moment someone demonstrates any evidence of God I will no longer be an Atheist. Also, I have to make a minor correction: I’m an...

Saying Goodbye to Glaciers’: The Impact of Glacier Retreat

Saying Goodbye to Glaciers': The Impact of Glacier Retreatphroyd: Click To See Video! Phroyd

Threats, bullying, lawsuits: tobacco industry’s dirty war for the African market

Threats, bullying, lawsuits: tobacco industry's dirty war for the African market

I seen a lot of bullshit about the recent shooting at the repubs living it up at their baseball game. Give the real from a pan African perspective. Damn near no one give a fuck when politicians kill and restrict the lives of thousands with legislation but when they get a cap bust in they ass which happen once in a blue moon, it’s “we all need to come together, we all, family, stop the violence”.

The first reports coming out of the shooting stated that the shooter was taken into custody, later that afternoon it was stated that he was killed on the scene; that small discrepancy gives me...

Killer Mike is officially a piece of shit for defending Bill Maher. You called him out on his shit way back talking about black folk aint ready for revolution. I know you a real one cause you be spotting the bullshiters when everyone else is on their bullshit.

#HandsDownKillerMike! http://pitchfork.com/news/73955-killer-mike-cool-with-bill-maher-after-controversial-remarks/

Forget the Flowers. This Mother’s Day, BLM Activists Are Posting Bail for Dozens of “Black Mamas.”

Forget the Flowers. This Mother's Day, BLM Activists Are Posting Bail for Dozens of "Black Mamas."

so my white mother shouldn’t have saved my brother’s life from his abusive child molesting father simply because he’s brown. she should have just left him because that’s what’s politically correct. even in this “isolated case” where he was being sexually abused. alright. you make me sick.

First, I’m assuming you are White.? Second, since you White I’m assuming everything else you are saying is an absolute lie.? Third, I hope the sickness that I provoke in you is terminal, cuz you...

North Dakota Has Experienced More Than 700 Oil Spills in The Past Year Alone

North Dakota Has Experienced More Than 700 Oil Spills in The Past Year Aloneshychemist: With the highly controversial Dakota Access Pipeline expected to start operations this week, the latest reports...

Are african immigrants who immigrate to United States also considered colonial subjects ?

Yes. And if they don’t wanna accept that, I just what for White America to learn them.I employed this Sudanese waitress at my Vegan restaurant back in the day, she swore that I wasn’t African,...

What are your thoughts on Immortal Technique? I think you too would have a very informative and enlightening conversation. Althought you don’t vibe with Dr Umar, you too would have good dialogue as well…. Your thoughts on Dick Gregory? He seems out of his mind. Lol. But what do I know.

I really like Immortal Technique, but I don’t like him using “nigga” in his rhymes, that shit ain’t cool. I didn’t grow up in NYC, and I almost got into a fight when this Puerto Rican...

you are are wrong about the clay eating, if you actually know the the powers that those clays have in regard to beauty you will find your self overdosing your self on them, so my recommandation ask. those clays holds secret which most primitive cultures keeps to them self if you uncover them, you will never ever ever buy any cosmetic over the counter again.

OK, fine, enjoy your clay. I don’t even remember what I said about eating clay anyway.

Brother Diallo, after Fidel Castro’s 90th birthday what can we learn from his resilience? The United States tried to assassinate this man hundreds of times. Was Castro lucky or was it something else?

What we can learn is that Socialism works, and that even an isolated, surrounded, and besiege little island can endure employing Socialist economic and social programs and policies. But Cuba was not...

The great legendary boxer Muhammad Ali passed away a couple of months ago ! I realized that he just traded a slave religion/name ( he was Christian and his previous name was Cassius Clay) for another slave religion Islam ! In your opinion was Muhammed Ali ill informed about the history of Islam imposed by the arabs (who are genetic cousins of the european christians) ? And if he would have embraced a african religion would he have been a cult in africa and the african diaspora !

I’m not sure what Ali know about the history of Islam in Africa, or if he know about the ongoing Islamic Racism and Imperialism in Africa up to the time of his death. I know the NOI, which brought...

Can you give some context on who Matthew Stevens is and why he is committing these illegal acts against you and the kids?

Damn, I don’t know if I should reopen that can of worms cuz he’s been quite so far this season and I don’t want him vandalizing our spaces again…, but then again he’s harassed and...

Yo Diallo, what is your opinion on keto/paleo diets and all that other rich ofay bullshit?

Oh, it’s totally Ofay Bullshit!It ain’t nothing be a rebranded Atkins Diet; a bullshit fad, nothing more. Especially if you Black, we ain’t and never were cavemen; so why we tryna eat like...

What do you think about Jill Stein? Who do you think we should vote for? Should we even vote?

I think she was the best candidate, with the best political platform, running for the best party in the 2017 presidential race.I think Black people should have voted for Jill Stein, and all other...

What exactly is Asili Culture ? Could you explain it in your own words ?

Asili is the seed from which any particular culture is spawned, nurtured, and cultivated. The people, environment, and timeline of an identified people; absent of or prior to alien influences. The...

Is there a hidden agenda to Brexit ? Also will there be a chain reaction in the European Union ?

No, the Brexit is as Racist, Xenophobic, and Jingoistic deep down as it appears to be on the surface.The only reason people are surprised by Brexit is because they don’t teach the History and...

Is it possible to built eco friendly cars,motorbikes,trucks,airplanes or should we abondon all those things in order to save the life sustaining capacity of this earth ? And what about Technology in general are you against it ?

It is essentially impossible to built eco friendly cars, motorbikes, trucks, or airplanes. Even if you manage to fuel them using bio-fuels, electric batteries, or hydrogen cells. Over 7 gallons of...

Mainstream Media Finally Exposes Elite Pedophile Rings in a Horrifying Episode of Dr. Phil

Mainstream Media Finally Exposes Elite Pedophile Rings in a Horrifying Episode of Dr. Philfelix2001a: jerseydeanne: wageronliberty: anarcho-individualist: getinvolvedyoulivehere: I wasn’t expecting...

Tell me, how can one be a Pan-Africanist and Pro-homosexual, Promosexual at the same time. My question has nothing to do with homosexuals bedroom activities. I see you completely failed to provide a realistic well rationed reply when you were asked if you were a pro-homosexual or anti Homosexual, you completely curved the question and just jumped to conclusion and directed the question to how a man felt about 2 of the same sex do sexually, rather than giving a direct answer.

I wish you’d just come outta the closet and stop trying to work out your struggles with your sexual and racial identity on my blog, Anon. SMH.I’m personally anti-Homosexual, thus all the sex...

Do you consider Genghis Khan a Imperialist & mass murderer ?

Yes. But you know what’s worse than Genghis Khan’s crimes; John Wayne playing Genghis Khan in YellowFace.

if you were in charge of a country, and could implement any rules/ethics, what would they be?

It depends, am I a dictator, a president with two co-equal branches to contend with, am I a prime minister who has to build a governing coalition?What I’d do as a head of state is the same, but how...

White Allies…

I don’t really understand this “White Ally” shit. Sorry.Maybe yall Liberals can help me.First of all, if I don’t know nothing about alliances I know that they are MUTUAL; all...

If you talk about the White race being hyperaggressive do you acutally mean the Eurasian race in general since Whites evolved in western asia ? Also does this explain why western asians (arabs,persians,turks etc…) had Empires and tribal wars just as their european cousins ?

Yes, I mean White and off-White people; but those people from Western Europe seem to have a leg up on even their Asian cousins when it comes to Hyper-Aggression.But to be fair, there were White...

Brother Diallo, after the events of the past few days, I think in the next 60 years America is going to look like some of the worst war torn places in the Middle East and Africa today. Do you agree or not? Police just used a bomb robot. How can black people prepare?

The biggest impending threat is Global Warming and Climate Instabity; which will lead to food shortages, further contamination of the air and water, and an exacerbation of all standing conflicts in...

Your point about the use of media cycles to cover up certain news stories like the FBI’s decision not to prosecute Hilary Clinton was poignant. Alton Sterling, a black man, was killed by the Baton Rouge police yesterday. Black people are killed in the U.S. everyday without much fanfare. The media coverage of Alton Sterling’s killing makes me wonder is the media attempting to bury the FBI’s decision to not prosecute Hilary’s criminal acts deeper in the news by covering this brother’s murder.

Damn, this shows how far behind in answering my blog questions I am. SMH.But yeah, there are ongoing atrocities commited aginst Africans everyday on US soil, but they only give national media...

The crazy thing about July 4th or White peoples Independence Day as Chris Rock said it I know you don’t like him lol, is that these whites celebrate a day when they overthrew their british overlords by force. but despise and can’t relate to black folks dong the same to them.

Well, Whites were not just fighting for Independence back in 1776, they were fighting over the control of a Genocidal Colony. The war for Independence was not a way of Liberation, it was thieves...

Have you heard about the African Union (AU) rolling out an All-African Passport to increase unity, trade Options between the 54 african countries !? What’s your opinion about that ?

I heard about it, I thinks it’s cool, but greatly inadequate; Africa should have a common currency, a unified military, a secured African trade bloc. Africa should have already reintegrated its...

Bro. Diallo, I have listened to and read your critiques of the black misleadership class and I wholeheartedly agree with and share your analysis. However, I would like to know your thoughts on what leadership is. Do you think leadership should be collective? Do you totally reject the idea of individual leadership and/or leaders? How do you think we as a people should go about systemically developing grassroots leadership?

A people should be lead by their vision and mission, that’s it.Who is the Leader of America? Who’s the Leader of Europe? Who’s the Leader of the Zionist Movement? Who’s the Leader of...

Diallo You speak about building alternative systems and institutions. How can we be protected after we build them if we’re still behind enemy lines? We have no Nation Diallo You speak about building alternative systems and institutions. How can we be protected after we build them if we’re still behind enemy lines? We have no Nation States to reach out to or have our back if the funk jump. to reach out to or have our back if the funk jump.

That’s particularly easy; Racial, Religious, and Ethnic Minority groups have built institutional power, secured control of resources, and erected infrastructure within larger (and hostile) Systems...

why do you hate white people?

I don’t hate White people, if you look at history the greatest and most consistent threat to White people are other White people. Why do yall hate each other so much? Why have White people...

what’s your point of view on Britain leaving the European union?

Until the White Colonial nations give true autonomy and full reparations to Africa and the African Diaspora everything they do will crumble, including the weak ass European Union and the Euro Zone.

What are your thoughts on #Brexit from a Pan African perspective? I tried to understand this stuff but I really don’t.

Here’s the core truth: The EU was all about Germany doing economically what Hitler failed to do military: domination of Western Europe, the UK people don’t understand this, they just voted to...

Greetings, why is western media so obsessed with portraying Africa the way it does?

You’ll notice that all abusers work to portray their victims as being the cause of the abuse; wife beaters, rapist, pedophiles, and capitalist swear that their victims had it coming, that their own...

Brother Diallo, You’ve done any research on Detroit? Why is the place so fucked up right now? Matter of fact, it’s been fucked up a long time. Right wingers say it’s all black folks fault.

Well, Detroit hasn’t been fucked up for a long time, it has actually fallen off within a single human lifespan. In 1960 Detroit was literally the richest city in America! No lie, look it up; I...

The FCC Just Blocked Privacy Protections For Comcast And Verizon Customers

shihtzuman: The rules would have required giant internet providers to adopt reasonable security measures and to notify customers when data breaches...

On the Milo Bus With the Lost Boys of America’s New Right

On the Milo Bus With the Lost Boys of America’s New Right

I read a lot of your post on living a healthy lifestyle through veganism. I have tried to live a healthy lifestyle, but I drink a lot. I think it’s addiction, but it’s so much more. Basically what is your analysis on drinking, drugs, and why people (especially black people) fall victim to addiction?

The world’s top researcher on addiction is Gabor Mate, he’s determined that addiction has less to do, if nothing to do with the drug or substance people are addicted to but social and internal...

Lets say you make it big. You have your own program on cable television and is receiving massive support, and gaining popularity. Should we assume you’ve been compromised and no longer viable to the movement?

First of all (in my Kevin Hart voice); you don’t have to make assumptions when there is evidence available. It would be obvious if I sold-out, espcially in the context of the Bro. Diallo Show.I...

why is haiti so poor?

Well, there’s a few reasons. The main reason Haiti is poor because Haiti is the Capital of African Diasporic Struggle, and therefore will not be allowed to form a sovereign government, develop...

We need a new conspiracy corner fam. You need to describe the Trump Hillary election and what the elites behind the scenes are planning with this shit.

The Elites are experiencing an internal class war and Heelary and Buba Trump are their clubs they are using to bash each other; all the rest of us are just collateral. This is a simplified...

What were some of the problems that blacks faced at the time of the great depression and how did it effect us in our struggle?

There was an old joke about how Black people didn’t know there was a Great Depression until they say Wall Street raining White men. But there’s a more accurate saying from that era the...

Is Black Lives Matter just another integrationist movement?

Yep. Integrationist & Reactionary.So far, but the Black Panthers and Black Liberation Army grew out of Integrationist Movements like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Student...

Why haven’t you been on SaNeterTV yet? I think you’d be a great edition.

It’s funny, when Sa Neter used to sell VHS taps on a fold out table in Harlem he used to have some of my lectures; but since he went online I think the nature of his content changed. It’s more...

This Seti and Johnson conflict is disappointing. Both men are very questionable and have said questionable shit, but I do at the very least give them credit because they are public with their beliefs, ideas and stances and that shit is very dangerous. Yet, this conflict is clownish as fuck. Both men claim to be leaders too. smh. You think black folk still need leaders or should every individual black person figure it out for theyself? I’ve heard good arguments for both.

If you are disappointed in Seti or Umar then you haven’t been paying close enough attentions to them; their demagoguray has never been hidden. They been behaving this way since they emerged on...

What’s the difference between Hilary and Trump?

Heelary is White.Trump is Orange.Heelary is a polished Fascist, Racist servant of White Elites.Trump is an unpolished Fascist, Racist servant of White Elites. Heelary is aligned with the New White...

What do you think about pro-lifers?

They ain’t pro-life, they are anti-White-Women-Abortions. I don’t know why they don’t just admit that shit and stop being the lying ass, hypocritical, contradictory muthfuckas that they are.

I see you, appreciate your effort. Question: Would you go to a youth pastor, in a Christian church, who is actively trying to get kids who know nothing more than sneakers and gang banging to change their lives around and worship God, and challenge his beliefs? Could you replace his role? Or, might there be ‘levels’ of understanding that one may/must go through, where beliefs have their time and place, regardless of if some choose to die with or transcend those beliefs?

As much as I hate how many Black youth are having their minds destroyed by the Religious Indoctrination, I wouldn’t go to a youth pastor in a Christian Church & object to what they are doing....

Have you seen the TV show “live PD” and what’s your thoughts on it

I ain’t never seen or heard of it, sorry.

With the revelation that global whiskey brand Jack Daniels was created with the help of a black man Nearis Green 150 years after it was created, I wonder what else white folk are saying they built and invented while it really was invented and built by black people?

The (unwritten) Law and Practices dictate that all things created by a Slave is Property of their Master. So, when a people are enslaved, their time, talents, and resources need to be given over to...

Do you believe labor is a commodity?

Short Answer: Yes. I don’t believe or condone it, but that’s the reality. Labor is a commodity. Expansion:Under Capitalism everything is a commodity, or commodified.Separating People from...

What are your thought and opinions on Common? Did you hear his latest freestyle on swaysuniverse? It was some real talk.

Disclaimer: I say all of this as a fan of Common from day one, I still got my “Can I Borrow a Dollar” CD in rotation.I didn’t listen to his freestyle on the Sway show, or whatever. I ain’t...

Why do whites try to bring us down to their level of insanity by trying to cite the Rwandan Genocide as evidence “see blacks commit genocides too!”. I’m not even sure if it was really a genocide or not, even if it really was, one historically recorded genocide doesn’t even bring Africans near the white people insanity.

There was no genocide in Rwandan, one could call it Fratricide; killing of one’s own brothers and sisters. The Hutus and the Tutsis are the same damn people, they had been intermarrying, and...

Brother Diallo, What keeps you from goin full on Mark Essex or Chris Dorner? I know everyday you read and see racist comments and lies based on white domination, especially on the internet. You probably see even more of it than the average person because you are a politically conscious black male. What keeps you focused? BTW not judgin Essex or Dorner at all. I won’t be one to judge an oppressed person for how they responded to white shit.

The simple answer is: I’m not a Reactionary, I’m a Revolutionary. But I don’t think it’s fair to put Essex and Dorner in the same box. Even if I went on an armed rampage I would never be a...

Should women attend the Women’s march in Chicago?

White women should, Trump is they fault. It’s not a mess that our Sisters are responsible for cleaning up.

Good brother Diallo. How soon before there is a total blood bath in the United States? Most all of the conservative or libertarian states aka “red states” as you told us before which is just polite ways to say psychopath were part of the confederacy. While blue states were part of the union, and as a matter of fact the “left” in this country is just right wing that uses softer rhetoric. So how long before American Civil War part 2 or am I just alarmist and off the mark? Peace fam.

How soon? The blood bath in the United States started in 1620! You late.Or maybe you want to know when you will be directly and personally impacted or harmed by the violence needed to establish and...

What are your thoughts on neutrality and objectivity? Also what are your thoughts on objectivism?

Howard Zinn stated that; “you can’t be neutral on a speeding train,” and I agree with him. Also, Kwame Ture stated that “if someone is attacking your mother, and you fail to take sides,...

Apparently Muhammad Ali’s “IQ” is 78, which according to the measurement makes him barely above retarded. But, he was an articulate and charismatic man. He was also clearly a wise man who fought for social justice and stood up for oppressed people. I think IQ is a load of bullshit.

Yes, IQ is some Racist, Eugenicist, White bullshit. I wasted a week or two of my life reading “The Bell Curve,” and even in that text they had to admit that IQ test were bullshit. They...

What are your thoughts on space exploration and colonization from a Pan-African perspective?

The earth has many infectious diseases (like Capitalism, White Domination, Ecocide, etc) that would spread to other planets and star systems if we did manage to colonize other worlds. So I think we...

Brother, I know you atheist, but would you be mad if there were a resurgence of African traditional faith and religions like Vodoun? I think the problem is that Vodoun isn’t all that structured and it’s been infiltrated and diluted by bullshit like Islam, especially in North Africa and Christianity I don’t know about Judaism but maybe that dogshit too. I know you would like everyone to be atheist, but human beings are not in our lifetimes going to fully abandon spirituality.

I have absolutely no issue with Africans embracing their own myths, folklore, dogmas, and fables. You are correct that all Native African Spiritual Systems are contaminated by Western and Islamic...

Diallo, some black guy on twitter went on a rant about how capitalism is the most productive system and how it’s not capitalism that’s the problem, it’s greed. he also said that all systems are corrupt and this corruption is greater in socialist communist countries and how those economies make everyone equally poor and mediocre. He also said if socialism communism is so great why are people from those countries migrating and rushing to come to the USA. Thoughts?

Tired old retorts. Those aren’t that New Negro’s own views; he’s just regurgitating his indoctrination, it’s really no point in trying to debate such a terminal Negro. Negros like that do...

Okay I read your piece on Alternative Lifestyle people and how the thieves of the world look at them. Of course I’m just summarizing what the piece was about, but that is not why I’m typing this message/question. I want to know 1 while I know that some of our people are “programmed” or “choose” to be active paparticipantsf an alternative lifestyle but how can you equate their “struggle” and “plight” with our systematic oppression? I have more questions but I’m out of characters

This is a little confusing, I have an alternative lifestyle: I’m Vegan, my wife and I home-birth and “home” school our children, we use bikes a a major form of conveyance, we grow much of our...

I know you have mentioned many times that their inherent death wish, constant violence, and the need to oppress and dominate in white culture means that if it wasn’t the African that white people oppressed, it would have been any other race. However, do you think white people actually envy the Black race and our different cultures in many ways? Even the way we look?

It certainly looks that way. I think Jeru the Damaja put it best when he said: “mock my appearance yet yearn for my essence.”

Why do other races come to America and get Established within a few years? Are they aided by the government? They Build up communities and it seems as if they become millionaires over night make every Penny off the black community. Hair nail shop. Gas stations ect ect

It’s the nature of the Immigrant, no matter where they go to “establish” themselves. No matter their Race.If you looks at Blacks from the US who move and live abroad they are more educated,...

So is China the most successful communist party in history? Or is it not even communist at this point? So much confusing shit coming from the way that nation is governed and organized. Also, what can current and future revolutionaries learn from China?

China had a Communist Revolution which allowed China to oust the Imperialist, educate its population, and industrialize the nation, but it did not construct a Communist economy or political system....

Greetings, why do you think western media is obsessed with portraying Africa the way it does?

Cuz it validates Capitalism and White Domination. The corporate Western media seeks to show Africans as unfit or incapable of self-governance, show African nations as impoverished and unable to get...

What are your thoughts on black folk that claim to see neither race and color?

I think they some lying ass muthafuckas. Most Black who talk that shit because their social or economic standing depends on them pretending to not see Race or color; and who am I to knock their...

What are your thoughts on Ayn Rand and individualism from a Pan-African perspective? Why do you think so many white people believe in libertarian ideas and what does libertarianism mean to you from a Pan-African perspective?

Ayn Rand was a grade-A sociopath who managed to turn her sociopathy into an incoherent social theory and ideology. Individualsim is a toxic Western fiction. The individual is a product of the...

Would you have been down for an armed Black takeover of some large piece piece of real estate in America for statehood for the benefit of all Blacks during the time that Malcolm X was calling for it, or would you be down for it now (theoretically)? How is it We have not managed this by this point?

Not really, cuz such a thing could be accomplished politically, economically, and culturally right now; so why resort to arms when simple coordination, planning, and organization will suffice?I have...

#DiallosConspiracyCorner : the General vs the Prince.

Is it just me, or does this super emotional, hyper-aggresive conflict between the General & the Prince have strong homoerotic undertones? I spent the entire summer beefing with this dude, face to...

Why do so many people say that even if you don’t like religion or are atheist, that you should respect religion anyway? Any thoughts on this? Do you respect religion even though you are atheist?

People think you should respect religion because they are socialized and indoctrinated into the notion that certain delusions and fictions carry as much weight as evidence and reality. Religious...

Hey. Is it crazy or unrealistic of me to suggest or envision an all black Afrika? Their is a large number of Indians, Arabs and whites that all oppress black natives. I personally want them all gone. Is that unrealistic with today’s globalized world. especially since it also suggests genocide?

I ride with the late Dr. John Henrik Clarke on this issue; he stated that Africa should be under African governance, and anyone who has an issue with African governance over Africa should be shown...

Brother Diallo, recent scientific studies on the brain have shown, btw I know science be on that bullshit especially as it relates to black folk but still, those studies show that the brains of mass murders and psychopaths is wired different. Since we know that white people collectively are the only group on the planet to commit genocide on every known continent does this mean these folks brain are different? If so what is the cure?

Yeah, Dr. Bobby E. Wright all of this scientific and historical analysis and condensed it into a pamphlet sized text called “The Psychopathic Racial Personality.” Every Black person should have...

What are your thoughts on women like Ro Elori Cutno and Nojma Muhammad?

I was accused of bullying Ro Elori Cunto one time. I was simply sharing her insane post and memes; I didn’t even know who the hell she was at the time, that shit just cracked me up, it was so...

Do you agree with Chinweizu that Africa must industrially develop, whether under capitalism, socialism or communism to sustain itself from future imperialist and colonialist in other to be liberated? Decolonizing The African mind was published in 1987 so how would those ideas apply now with advanced technology, and a growing African population? Not to mention Africom and Americas secret army bases on the continent. Is industrial revolution still the way for Africa? Can Africa remove its self fro

You question kinda cuts off at the end…As far as Chinweizu, all of his text are magnificent (except for “The Anatomy of Female Power,” that shit was bugged, interesting, but bugged); but...

Brother Diallo, I know you don’t like the wealthy elite, but let’s say you were a part of that class and you suddenly became woke what would you do with all your billions? Speaking of getting woke why do you think the wealthy black and African elite are not woke?

If I woke up with a billions of dollars; first thing I’d do is buy that pair of Vegan faux leather boots my wife been lusting after for like a year now, and a used XboX One with a used copy of...

Young Black Girl Dies In Police Custody – Authorities Offer No Explanation, Media Silent

blackfemmerealness: couplelookingforher2: theproblackgirl: Pictured: Sheneque Proctor, 18 years old at the time of her deathA young African American woman from Brighton, Alabama recently died in...

why do black people suffer from historical analysis and cultural consciousness? the only reason why i asked is because i think of the time during segregation where there was a black infrastructure. integration came and then it vanished, why couldn’t we just take it or leave it?

I’m assuming you are asking why we suffer from a lack of historical analysis and cultural consciousness.The truth is, Black people have a depth of analysis and consciousness that ebbs and flows but...

Soon….Trump POTUS.

I’m waiting for Trump to order the first drone bombing, to detain and lock up an immigrant family in a for-profit detention center, to assassinate a US citizen without trial, to ignore or...

#YouGoodMan: When the People Who Ignore You Accuse of Not Speaking Up.

Yall remember that #YouGoodMan bullshit, when people started the fallacy that Black men don’t express their woes, pain, and sorrow. When they started talking about how Black people don’t...

If Obama Was Your President, then Trump Is Too…

Americans are literally protesting the fact that they are moving from being governed by polished, Capitalist, warmongering, Racist, Fascist to being governed by naked, Capitalist, warmongering,...

BodayCams: Mass Survaillance is Oppression

Integrationist Activist and New Negro Organizations had Black folks in the streets demanding bodycams and dashcams for all US police officers.Now, them Negros was calling for this because they...

We Africans!

Question: why all of these populations and cults of Black people promote the idea that the original Native Americas, the original Arabs, the original Asians, and even the original Europeans were...

Those Mourning Castro…

Wow, do people love socialism, militant anti-imperialism, & African Solidarity as much as they love Fidel Castro?If not why exactly am I seeing all of this love for Castro on social media? Cuz I...

If Our Oppressors Were (other) Black….

If the global White Elites woke up Black in the morning we’d have a New Negro World Revolution on our hands by tomorrow afternoon.Much Black submission & passivity to White Domination is...

On Internal Enemies…

One of the main reasons the Cuban Revolution was successful & it’s leaders endured was because Castro, Che, and the Socialist leadership gathered up and ousted all of the damn Cuban Uncle...

Dancing the Slaves…

There’s this practice developed during the Maafa called “Dancing the Slaves.”The European Invaders, Colonizers, Enslaver, and Slave Ship Captains found that you needed to allow your...

Dietary Adaptations & Modern Delusions

Why when you are critiquing the dietary practices of Black people in the USofA, and promoting Veganism among our people these damn bone sucking, gristle chewing, bile sipping, flesh rendering fools,...

Abortions, Black Women, & Genocide.

diallokenyatta: Black Puritans love going on about abortion, and I know it’s just another opportunity to blame Black women, especially poor, under serviced, and under resourced Black women for the...

Obama: Free Our Freedom Fighters

Obama pardoned his final White turkey this week while our Black freedom fighters are still in prison or living in exile under constant threat from US intelligence agencies.The bulk of Presidential...

Why do a lot of whites think that America is some liberal jew communist conspiracy when America was founded by conservative principles and is still a conservative, war mongering, poor people hating, slave holding shithole? Also why do they pretend that jews aren’t white? Why do these whites think they are victims? Are they just too stupid to understand the world they live in or is it some other shit? Tell us what you think from a pan african perspective.

Whites have been unloading the blame for the ills of Western/White society on Jews long before the first Pilgrim murdered his first Native or raped his first African.It goes all the way back to the...

Fractal Architecture throughout the African Continent

eyemodernist: El Molo Hut, Lake Turkana, Kenya Classical architecture consists of mostly Euclidean or flat shapes and straight lines (bricks, boards, pitched roofs etc). Fractal Architecture consists...

You’re doing all this crying about trump winning, what would have been different if hellhairy clitorus won?

Listen you sexist Yurugu, you are barking up the wrong tree, I ain’t crying about Trump’s victory, I know Trump & Heelary were cut from the same cloth and serve the same agendas.You know,...

Who’s to Blame for Trump: Obama Is.

Trump is Obama’s legacy, if you wanna blame anyone blame Obama.Obama was elected with a mandate, and we also gave him a Democratic majority in the house and senate. Obama also entered office...

now that trump is prez are u leaving the usa?

Naw.The Systems and Institutions of White Domination and Omnicidal Capitalism are global, so there’s not where to run to, there is no sanctuary on this earth. There is not one piece of land, not...

Free Our Freedom Fighters Obama!

Obama is in a position to free all political prisoners (and drug offenders are political prisoners).He could allow Assata Shakur, Pete O'Neil, Edward Snowden and many others return to the US with...

You were wrong about HRC being voted into office. I’m sure you’ve got a lot to say. In 2016 got a guy who can openly run on a white supremacist platform and be elected.

Yep, I called for Heelary. Heelary did win the election but she was robbed, but that’s just poetic justice because the same tactics she used against Bernie in the Primary were used against her in...

Some of Heelary’s Black Supporters are: Woke AF.

Don’t simply denounce Heelary’s Black supporters as brainwashed, blind, fearful, or unconscious; it’s so much more complex that that.It’s really important to understand this...

Faux Feminist vs. Fool Feminist

Heelary is not a Faux Feminist, she is the real face of Feminism, she represents the real mission and predictable outcomes of Feminism.Feminism, despite all of its analysis, rhetoric, and promises is...

Boo! Of A Nation.

All these people here lamenting Boo! A Madea Halloween being the #1 movie in America while BOAN not reaching its expected earnings out the gate, these people really expect us to believe that if BOAN...

It is the most naive and obvious question, but how do you think we should geographically organize as pan-african revolutionaries? Bc all moving to Africa is delusional and invasive i think, but building within western territorial states (fronteers, constitutions etc) without participating a bit to reforms seems veeery edgy. I live in europe, and the few woke ppl here are quite integrationists. Not me, but i can’t figure out a debut solution, ideas? thanks, sorry if u already answered dat!

How can I have a competent response condensed to fit in the little blog box they allow me here? SMH.1. We need a Global Pan-African Revolution because Oppression and Ecocide is Global, it’s not...

What do you think about Booker T. (Kaba Kamene) ??? I always felt that he was the only person on Sa Neter TV that ever had any sense, a plan and was actually acting on these plans. Might be why he’s rarely on there.

Man, I ain’t really followed Booker T. since he was giving lectures for the UAM (United African Movement) in Harlem; that was way back in the late-90s and early 2000s. I don’t really follow the...

What do you know about the “Gullah Wars”?

I know the Gullah Wars are still going on, I know that. They just moved from using muskets, cannons, and troops to using economic displacement and Racist public policies. Oh, and the White...

How will you address “willful ignorance” in your book if you are still coming out with one. The reason why I ask is because in my everyday life I see people wanting to be blind to facts around them. I mean just having a conversation about anything outside of sports, entertainment, etc seems to be impossible. How does one pierce through “willfull ignorance”, to get real work done in the revolutionary process?

Shit, I really need to set a date for my text. It come out, one day….soon.As for Willful Ignorance, the best way to combat it is to change the fundamental material circumstances and...

From a Pan African perspective whats more important politics or science? What are your thoughts on the apolitical, especially white folk that say fuck politics, only science counts?

Politics is way more important than science. Politics determine the level of investment in science, the direction of scientific research and development, the implementation of science, the...

To Serve & Protect…the Status Quo

Police enforce the Status Quo not laws, justice, or morality. If you are not opposing, obstructing, & dismantling the dominant Status Quo you are not truly addressing Police Atrocities. We now...

When the missionaries came to Africa they had the Bible and we the land. They said ‘Let us pray.’ We closed our eyes. When we opened them we had the Bible and they had the land. Desmond Tutu

But it’s ironic that Desmond Tutu’s punk-ass would say that shit since he’s a fucking Catholic Bishop, and his treasonous ass supported and oversaw the Truth and Reconciliation Commission,...

Diallo I would like to know your opinion about the entry of military troops in Africa, specifically in Djibouti. I read an article about it and I think it is worrying. I mean that this may be only the first step to a full-fledged colonization

That’s Africom, which is just an offshoot of PNAC.The US and it’s Western/White allies are well past their first steps to full-fledged re-colonization of Africa. You have to research the PNAC...

why do you whine like a little bitch?

SMH. Your tough talk kinda losses its bite when you are trolling behind the Anon dude. I don’t actually whine, it just sounds like whining cuz you lack the capacity for critical thinking and...

i read about the people of mali actually hating mansa musa and also his bame being forbidden or something

Well, I share their sentiment, fuck that Arabized African, fucking glutton. #FuckMansaMusaOh, and if you got a link to that info, please share it with me. Thanks.

what do you think blacks would do if congress repealed 13 14 and 15 amendment and reinstated national slavery?

Protest. March.Pray.Submit.Pick Cotton.Snitch on Rebels. Just like we did last time. SMH. Just like we do now. SMH.

what are your thoughts on gandaffi

I think he’s dead.I’ve answered this question already, search my blog archive.

Brother D, do you think 9/11 happened the way the government and mainstream media said it did?! Also, why was Iran recently ordered to pay $10 billion to the families of the victims? Why not Saudi Arabia get blamed instead?

No, 9/11 was a False Flag SCAD (State Crime Against Democracy); at least that’s what all of the known evidence and research points to.The judgement against Iran for 10 billion dollars for 9/11...

What are the successes and failures of Castro’s time in Cuba, as well your thoughts on his influence on worldwide anti imperialist resistance.

Shit, man, that’s a books worth of shit; I’ll just give you 3 of each to keep it as short as possible.Castro’s Successes:1. Playing the Nuclear Powers off of each other: Castro was masterful...

What are you thoughts on Léopold Sédar Senghor, and also Negritude?!?!?

I’m not a Fan.Senghor was the prototypical Neocolonialist leader. He took over the apparatus of the Colonial State, sustained the Western ideological and institutional practices, and failed to...

I have listen to your little radio show and you are PRO STUPID, not PRO BLACK…IDIOT!

“I have listen…”: That’s improper verb agreement, you should have said “I have listened….” If you were listening while you sent this Hater-Ass message, you should have...

Register Race Offenders…

White Aggressors need to be labeled #RepeatRaceOffenders, and be#RegisteredRaceOffenders, and have no direct contact with non-Whites without direct & monitored supervision of armed Black men and...

I am the anon who said you were uneducated. I’m not white and the fact that you assumed that anyone critiquing you is white proves you’re a troll. And you proved my point about you being uneducated about genetics. You believe in some sort of lab genius African creating white people and others through splicing. You’re ridiculous. Extremist crazy people from other races and countries don’t glorify their fictitious past quite like the African ones ?. By the way, mutation is how evolution occurs.

First of all (in my Kevin Hart voice), muthafucka, you know damn well your ass is White. Talking about “African ones,” Black people don’t talk like that about themselves or each other. You...

What are your thoughts on individualism? Is it real or nah?

I reject and work against Individualism. Individualism is very real.Individualist are human emotional/material parasites.Individualism is the ideology or mental defect of people who extract from...

You’re clearly uneducated and know nothing about how genetics ?

Well, I know enough about genetics to use em to pissed off White dudes on the Internet. Haha, be mad, fuck you; wit cho neanderthal genes spliced with smelly dog DNA? & rapid ageing sequences?.

Which race is hated more worldwide, White or Blacks?

Good fucking question! Seriously.This is a hard one, so I gotta make a List. 1. Who has Colonized, Committed Genocide, and Invaded every populated landmass on the face of the earth: Whites.2. Who has...

Brother you said something very interesting in one of your shows. Something like, “it’s gotta be biological. That white people’s racism or hatred has been sustained for so long.” Do you think that the racism is a white biological issue? Some would accuse you of essentialism and being racist yourself. Do you think it even matter if it’s cultural or genetic? Hotep.

I think White Aggression has a both biological and deep seeded cultural component; but not Racism.Racism is just one of many manifestations of White Aggression. The first victims of White...

What are your general thoughts and opinions on western civilization from a Pan African perspective?

Western Civilization as just another Imperialist myth like Christian Piety, American Democracy, Capitalist Prosperity, Trump’s Genius, and Heelary Clinton’s Progressiveness. (Yes, I know that...

Why do you think it is better that instead of going to Africa, we stay in Europe to fight? There are many good targets organizations who are fighting for human rights, without distinction of race, religion, ideology. But with little success. My intention is go to Africa to work there like a local resident. I want to integrate myself in African society as far as possible. I will not stop working with the Spanish organizations fighting for universal rights, I will contact them. What do you think?

I think it’s better for Europeans to fight against Global White Domination and Capitalism in Europe because they have more mobility, access, opportunity, and coverage. From a strategic stand...

Why didn’t you marry and have kids with a white-caucasian-european woman? And how do you feel about some of the revered black ancestors that fucked around with white women, like Dr Clarke or Douglass? Do you share the opinion that some black folk have that they were traitors or weak? What do you think about black folks that marry or sleep with whites?

1. Because I’m not talented enough to play pro-sports or secure a lucrative record deal. JK! Naw, but in reality, I was groomed from a young age by the Black women who raised me to be seek,...

What are your thoughts on Donald Trump?

Here’s a picture of me in a shirt that reflects my thoughts on Donald Trump.www.africanworldorder.com

What in your estimation is the difference between black nationalism and white nationalism and why in your estimation do both whites and black think both are two sides of the same coin? Do you think black nationalism is the answer to black problems and is still relevant or not?

Black Nationalism is/or is supposed to be rooted in the African Cultural Asili, which is essential humane and ecological; like most other non-Western culture.White Nationalist is rooted in the...

Brother Diallo, can black people be racist? If not, why do white people believe black people can be or are? Thanks.

No, Black People cannot be Racist.White People that call Black Racist are engaged in Psychological Projection.

Do you ever get really depressed when you see the oppression of Black people around you? From being evicted and made homeless to the extrajudicial murders. Sometimes it gets really difficult and I start to feel hopeless tbh. You always seem positive and that’s a good thing, I like seeing that, but how? How do you do it? I also just get really angry sometimes.

No, I’ve thankfully have never had to struggle with depression. Seeing and being a victim of oppression enrages me, saddens me, but it also drives and motivates me; but I has never depressed me.I...

Appeals Court Rules Employers Can Ban Dreadlocks At Work

the-real-eye-to-see: That clearly sounds like discrimination #AbolishWageSlavery

SMH. The Jackson estate just sold MJ’s stake in Sony/Atv for 750 mil. Which means that shit is easily worth a good billion or more. And The Jackson estate is inherited by white kids Which means black wealth has gone directly into white hands. I will never understand why Michael refused to have biological kids.

Well, I’m sure the King of Pop would have wanted it that way. MJ didn’t want to be Black, or perpetuate Black either.MJ rejected Blackness, and only returned to being Black or acknowledging...

White supremacy is as real as Black supremacy. It’s non-existent, a figment of people’s imaginations. A false ideology. I wish good people could just ignore these fools that espouse racist theories. We need to unite the human race and make the best of our time on the planet. Why can’t we all just get along?!

Cuz you muthafuckas got everyone’s shit, the Wealth of Western Europe, America, Canada, Australia, and the client states of the Western Empires are the direct result of centuries of theft,...

Why do entertainers, sports players and actors, just entertainers in general get paid so much money?

Because the service they give to the Status Quo, to the Global Elites, to the Empire is very valuable. All entertainers ain’t paid. I know many working class artist, entertainers, and athletes,...

As far as presidents go where would you rate Barack Hussein Obama? Some have stated he’s the best president, some have stated he’s the worst. To be honest it’s mostly white people saying he’s the worst which makes no sense when you look at American history and toxic waste like Reagan and Dubya. So based on the details of what the man has accomplished and his failings based on every other president where do you put the man?

Obama was great for Israel, Weapons Manufactures, the Auto Industry, the International Bankers, Wall Street (Institutional Investors), the Saudi Royal Family, the Tech Monopolies, For-Profit...

Brother Diallo, do you think a real revolutionary could ever become president of the united states? Someone who really is anti-sexist, anti-racist, socialist, pro justice, and pro just being a decent fucking human being? Do you think this will ever be possible?

There have been many Revolutionary presidents. Revolutions are not inherently progressive, you can have repressive, Racist, White Nationalist, Theocratic, and even Capitalist Revolutions. Which...

Maaaaan… why do so many of our kinfolk support the NOI or take seriously anything that clown Farrakhan got to say? Do our kinfolk study history? Do they realize the NOI was traitorous from the start? That fraud I mean “Fard Muhammad” was a white man and that wasn’t even his real name? that Elijah Muhammad was a pimp. and pedophile? That Farrakhan is CIA and ordered the hit on Malcom? Why come black folk won’t simply ignore and abandon these agents, traitors and liars?

I’m assuming that most of your questions are rhetorical, and I don’t agree with all of your assertions disused as questions, but I do agree with some.Tell you what, since you naming names, repost...

Brother Diallo, whites claim they invented most everything. I’m sure you’ve seen the list these racist whites spam showing how they invented everything from air conditioning to the bulk of mathematics. Thoughts on this?

I don’t bicker or debate with White Nationalist (unless I’m using them as a soundboard to drive home a point to a larger more relevant audience), because no matter how many facts, how many Black...

Your view on White couples adopting black children ?

I stand in total and absolute opposition to White people adopting Black children. Whites have a consistent and unbroken pattern of predatory behavior towards Black people, therefore they should be...

What’s happening brother. Are you surprised that “A Spook Who Sat by The Door” haven’t been remade yet?

Shit, I’m scare they’d fuck it up if they remade it, they would have Oprah producing it, have Tyler Perry directing, and have Kevin Hart playing the lead role. Fuck that shit. They keep...

Go Vegan, Be Vegan!

Your meat consumption isn’t just about your personal taste, if you consume meat you are needlessly contributing to the destruction of entire ecosystems, the needless slaughter of billions of...

Brother Diallo, I know you have been studying history for a while, so why in your educated opinion,is it that whites whenever they encountered new peoples and new cultures always sought to dominate them rather than cooperate or partner with them? History books either avoid or don’t fully address this question.

In all my years of study I have not found one instance in history where White people have encountered other, or outside cultures, races, nations and did not embark on a campaign of conquest,...

Have you ever heard of race realism or HBD;human biodiversity? What are your thoughts on this from a Pan African perspective? Do you agree that race is biologically real and that behaviors and entire cultures are based on genetics or belong to a defined race?

Yes I’m familiar with HBD, it’s Racist bullshit, it more pseudoscience, which White Racist have been engaged in for centuries. Whites have been trying to excuse the world-wide ongoing...

Why have AAs been able to build institutions post slavery, yet opportunities were not in place for Afro Latino/Caribbean/European people?

I’m not really sure what you are talking about. Many institutions that appear to be AA on the surface like the NAACP, HBCUs, or the Black Church are not actually AA, they are White Institution...

I made a mistake with the previous question. I meant, what can Black immigrants do to build up their home nations whilst living in the West?

Black Immigrants simply need to join or organize Revolutionary Pan-Africanist Organizations in their adopted nations, plus all the stuff I listed in the previous response.Black Immigrants when they...

What do you think Black immigrants can do to improve the state of their nations?

1. Embrace Pan-Africanism.2. Reject Colonial Borders.3. Reject Capitalism.4. Reject Tribalism.5 . Reject Christianity.6. Reject Islam.7. Embrace the African Diaspora.8. Reject...

Your new name should be Buck Dancer Diallo.

Really? That’s what you come back with. I gave you a W.R.I.T. Score of 8.5, & this is the gratitude I get? SMH. Revised W.R.I.T. Score : 4 : Below Average.

how come you always rant and bitch about white supremacy but never about yellow or asian supremacy?

First off, there is no such thing as White Supremacy, I actually rant, bitch; or as I like to call it; expose, critique, expose, and oppose White Domination, White Aggression, and White Pathology. ...

On Rape…

A Black woman asked me: “What is rape?” (She also said some other stuff about “regret sex,” false accusations, and other shit.) My response was harsh, but I don’t regret...

Black Puritans…

Black Puritans / Toxic Black Nationalist / Afro-Sexist: be all like… Black children impoverished, malnourished, & sexually abused all over the word = silence, no agenda, no outrage. Rich Black...

Young Thug In A Dress: A Non-Fucking-Issue!

If our parent’s, uncle’s, and aunt’s generation survived Little Richard I’m sure our children, nephews, and nieces will survive Young Thug. It annoys me that we are literally...

Diallo’s Conspiracy Corner: Femininity Is Not The Enemy.

Just imagine if the White man conspired to destroy Black Manhood through entrenching sexism, misogyny, & an open hostility towards femininity within Black men. What if the best way to do that...

On Civil & Human Rights….

Why do people talk about their Rights when engaged by the police?This is a serious question, like, am I the only person who understands that the U.S. Constitution is just window dressing?I mean, you...

How come so few black folk actually know or are aware of past or even present brilliant black scholars or better yet actually support them and implement their teachings? So few Africans know about Frances Cress Welsing, Neely Fuller, Claude Anderson, Dr. Ben. or John Henrik Clarke

To be fair, it ain’t just Black folks, and I don’t mean to be on some #AllIlliteratesMatter shit when you asked me about Black people specifically, but I think this is relevant.The US is now a...

Nancy Reagan just died at the very old age of 94. Thoughts? So much for karma. The savages who do evil somehow live the longest and in comfort too.

I went through the D.A.R.E. program, and I got me a “Just Say No” button at the end of it. SMH. You right about NR and her husband being some evil ass muthafuckas. I thought those Trap Queen...

What is up with the obsession with STEM? Many people from all backgrounds say anything other than science, tech, engineering and math is worthless. Then we have schools defunding the humanities, philosophy, art, political science, history is getting neglected. Then we have some blacks saying what we need is more blacks in tech, and that will get us towards liberation, but back then blacks were saying we just need a good classical education(humanities), and look where we’re at today.

STEM is trending because Black people have been indoctrinated to serve the needs, comforts, and interest of White people since we were enslaved by White people. We have come to measure our humanity...

What are your thoughts on Ronald Reagan? Why do a lot of whites love him even though his policies also ruined their prospects?

Ronnie Ray-Gun (as Gil Scot Heron called him) was a B-list celebrity who was assigned the role of POTUS by the elites in the early 1980s. By the time he won his second term he had already shown...

Do you think HIV is a myth or blown out of proportion in the black queer/sgl community? The CDC says 1 in 2 blk men will get HIV on their lifetime. Bullshit. This is entering conspiracy territory here, but what’s good bruh, you down for the ride?

Yes, the creation, propagation, and treatment of HIV and AIDS are full of myths and distortions, not just among Black LGBTQ but among all Africans across the globe. Also, since the 80s the Western...

What is your take on the role of the academy (meaning colleges and universities)? Do you think they help black people or hinder black people from making true strides toward self determination?

“The (White) schools and universities can train us, they can give us the skills we need, but they cannot education us, education must come from your community, (from your own culture).” - Bobby...

A Revolution Deferred: Mandela’s Legacy & the ANC’s Treason.

A Revolution Deferred: Mandela’s Legacy & the ANC’s Treason.

Brother Diallo, do you think it’s essential for black liberation to learn to speak African languages? Most black or African people around the world speak oppressor, invader and colonizer languages, such as French, English, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese, German and Arabic. There are some news reports saying it might be beneficial for future Africans to learn to speak Chinese. Thoughts?

Shit, I hate to say this….but….Naw, it ain’t essential. Now, before you report me to the Coon Police just allow me to explain my view. There was a time when Africans only spoke African...

Do you think Bernie made a huge mistake with his “ghetto” comment and not doing more to reach black voters like HC is doing?

I know this response is way late, but Bernie could never out Pander Heelary cuz the Clintons been pimping the Black votes since 1992. Bernie’s “ghetto” comment didn’t matter one way or...

What avenues can you recommend for the pan-africanist intersted in psychology and helping others heal from trauma on an individual and collective level? Thanks..

From a radical point of view, you want to go to the source of the trauma, not just target the symptoms of trauma. The sources of our Trauma are the Systems & Institutions of Global White...

#TeamPussy

I was called a “pussy” today (online). It has been a really long time since this has happened, like over a decade. I thought we were embracing the Black Feminist & Africanan Womanist...

Serena and Venus Williams lose first-ever Olympic doubles match

Serena and Venus Williams lose first-ever Olympic doubles matchThe Ancestors have spoken!!!The Williams Sisters, and all other African Athletes need to heed my call...

What should black parents and families do? What solutions are there?

Do about what? Oppression? Poverty? Education? Health & Wellness? That’s kind of a vague question. There are solutions; but what problems are you asking about specifically? I’ll just...

#KorrynGaines!

How long did the cops and Feds wait during the Bundy Ranch standoff and the Oregon standoff, while facing down White men armed with military grade weapons and openly threatening the authorities?...

Why are you so skinny? lol. But for real speak on it because so many of our African brothers and sisters neglect their health. And we need strong and healthy bodies for the revolution.

LOL! It’s funny cuz I was just telling someone I don’t come from Skinny. My people are big people. I don’t really strive to be skinny, I don’t watch my weight or none of that. I walk a...

In your opinion, is racism permanent?

No, Racism is relatively new to the world, most of human history advanced without Racism.Now, there will always be prejudice, xenophobia, and bias; but the Institutional Power needed to erect and...

How can Haiti be free of it’s chronic problems and issues and become the powerhouse of African liberation that it’s supposed to be in your opinion? I find it deeply disturbing and distressing that there doesn’t exist at least one strong African superpower nation/territory on the planet. Haiti should have been that land as it’s was the first and only successful establishment of a free black republic founded by enslaved Africans.

I think so, and the Western Imperialist Powers agree with me; or else why would they invest so much time and resources in suppressing Haiti’s people?I also agree that we need community, regional,...

The Revolutionary 1%…

If 1% can rule and oppress the rest while holding the majority of the world’s wealth and resources under their direct control, why the hell are we always complaining about and using “lack...

Bad Cops Only.

If there was such a thing as “Good Cops” there would be thousands of corrupt police officers tried or incarcerated after being reported, detained, and arrested by other officers. Show me...

what are your thoughts on white genocide?

There is no White Genocide, not even according to the White definition of Genocide, which is pretty stupid.Now, Whites are victims of Fratricide; because the only existential threat to White people...

Why do leaders of revolutions find it so hard to transfer power to their peers in a nonviolent manner? Why did Castro refuse to transfer power to one of his loyal compatriots especially those competent in governance and finance? Why hasn’t Mugabe done the same, why did Kim il Sung create a monarchy instead of fulfill the true aim of communist revolution?

That’s because the Revolution wasn’t/iisn’t over. The Oppressive powers that Castro, Mugabe, and Kim Il Sung fought are not only still standing, they are still on the offensive against these...

rudy giuliani cleaned new york nigga. new york used to be a jungle especially with yall jamaican “rude bwoi” acting like monkeys. giuliani shipped all yall black asses out the country. new york safer than ever. chicago need a giuliani. ship u monkeys wherever yall came from.

Actually, NYC is still home to the biggest criminals on the planet; the Wall Street Banksters, Hedge Fund Parasites, and the amoral bureaucrats of the United Nations. These are the...

What are your thoughts on Deray Mckesson?

He’s Bayard Rustin reincarnated. That means that we’ve progressed enough that a Gay Black man can openly lead a movement, instead of employing a figurehead like Rustin had to do with King. It...

What are your responses thoughts on David duke from a pan africanism perspective? He’s endorsed trump and stated voting against him is treason to European heritage.

David Duke is not a problem, and not worthy of our fear or focus. We long learned how to deal with Open, Honest, and Blatant Racist. We’ve long took to knocking the shit outta White dudes like...

do you have any books that you could suggest for black teens trying to become revolutionaries?

1. Blood In My Eye by George Jackson2. The Community of Self by Dr. Naim Akbar3. Carlos Cooks & Black Nationalism: From Garvey to Malcolm by Robert Harris4. The Falsification of Afrikan...

Patriarchy or Matriarchy?